NewsInternational Rental Insights: Japan

Introduction

Inspired by a Brookings series reviewing rental housing globally (link), we’re creating a series looking more closely at what we can learn from rental systems and regulation around the world. The series will focus on rental regulation, but also touch on the housing sector in general. While this series will primarily focus on how rental tenancies are regulated and the different forms tenancy structures can take, we believe the most critical factors for improving housing outcomes is an abundant supply of housing, facilitated by a more elastic housing market, efficient regulation, and market-based resource allocation.

Rental Housing in Japan:

Rental Housing Market Overview:

Japan’s rental system is shaped by a blend of formal legal categories and longstanding customs. While protections exist for both tenants and landlords, the legal structure appears to be more driven by societal norms and mutual agreement between tenant and landlord than specifically set rules. Housing in Japan is shaped by a few different factors

Tenancy Law and Lease Structures:

Japan recognizes three primary types of rental agreements:

1. Perpetual, open-ended leases that continue indefinitely unless terminated with cause;

2. Periodic leases — the most common type — typically structured for 1–2 year terms and automatically renewed unless a landlord provides just cause for non-renewal;

3. Fixed-term leases, introduced more recently in 1999, which are not subject to automatic renewal and carry additional procedural requirements.

For perpetual leases, standard termination notice is three months for tenants and six months for landlords, though the parties may contract alternative notice periods. Landlords require just cause for termination — such as demolition or personal use — whereas tenants may end the lease without cause. Periodic leases generally include negotiated termination clauses. If the landlord does not explicitly reserve a right to terminate, they cannot deny renewals or end the agreement unless for tenant non-performance. Some leases specify mutual termination clauses with three months’ notice, but the law prohibits excessive requirements, such as six months’ notice plus large termination fees. For fixed-term leases, the contract ends as written, but landlords must still provide notice of non-renewal six to twelve months in advance. Tenants may terminate early in cases of hardship, such as job transfers, medical needs, or family obligations.

Rent Regulation and Increases:

Japan does not have a structured rent control regime. There are no legal limits on the frequency or amount of rent increases. If a tenant rejects a proposed increase and the parties cannot agree, the landlord must apply to court to justify and enforce it. In the interim, the tenant continues paying the previous rent; if the court eventually approves the increase, the tenant owes the difference retroactively with 10% annual interest.

Rent is generally paid monthly in advance. In practice, rent increases tend to occur at lease renewal. Both landlords and tenants can request changes, but if there is no mutual agreement, the issue must be resolved via court or civil mediation. Accepted grounds for a rent increase include changes in property taxes, market property values, broader economic conditions, or evidence that the current rent deviates from surrounding comparable units.

Renewing a lease often includes a fee equivalent to one month’s rent, even if no rent adjustment occurs.

Deposits and Commencing a Tenancy:

Leasing a unit in Japan typically requires several upfront payments. Tenants are usually expected to pay the first two months’ rent in advance. Refundable damage deposits are common, ranging from one to three months’ rent. In addition, landlords often request non-refundable “key money” — usually one to three months’ rent — as a condition of entering the lease. An agency fee of up to one month’s rent is also commonly paid to the broker facilitating the lease.

Most leases require a guarantor, and tenancies are generally limited to family members. Subletting is not permitted. Pets are commonly restricted, and any modifications or renovations to the unit require landlord consent.

Discrimination based on age, family status, or disability is not prohibited under Japanese tenancy law. This contrasts with jurisdictions such as Canada, where such discrimination would violate human rights legislation. As a result, tenant selection criteria may include factors that would otherwise be legally protected elsewhere.

Uniquely, landlords in Japan are legally required to disclose “psychological defects” such as previous suicides or murders in the unit — a requirement that reflects cultural sensitivities.

Maintenance, Operating Costs and Tenant Rights during a Tenancy:

Tenants are responsible for minor maintenance and small repairs, while landlords are responsible for larger repairs and infrastructure. Appliances, particularly major ones, are often excluded from rentals.

Utility costs are usually borne directly by tenants. Property taxes remain the responsibility of the landlord. However, in condominium-style buildings, monthly service or management fees — covering cleaning and shared electrical use — are typically charged to tenants. These fees are often treated as separate from rent and vary by building.

Move-out procedures typically include a cleaning fee, often billed at a flat rate of around ¥1,000 per square metre (approximately $1 per square foot).

Housing Supply Conditions:

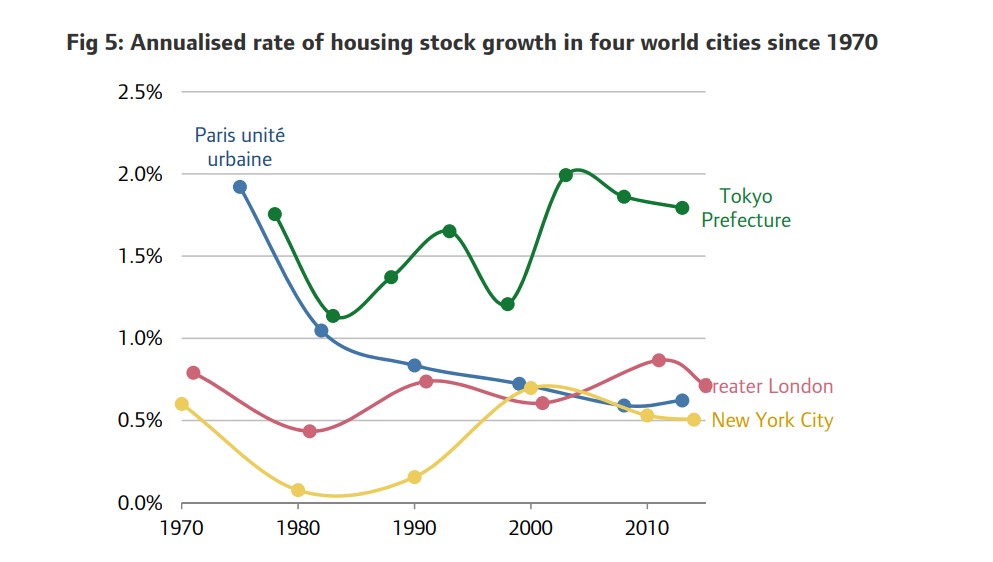

Japan has a unique planning system with centralized national zoning that comprises of approximately 12 categories. The system is like co-centric circles with each larger zone including the allowed uses of the prior zone but adding additional – with the broadest zones allowing heavy industrial. This contrasts to many western planning regimes where planners try to designate very specifically what can be built – down to the style or color of the building through conditional approval processes. The density and height calculations are also more mechanical in Japanese zoning. This combined with Japan’s seemingly low cost of living has lead many to theorize that de-localization of land use leads to more construction and housing supply (Sorensen, A. 2003). This chart from the Greater London Authority shows empirically an apparently strong ability for Tokyo to add housing, despite a tepid real estate market.

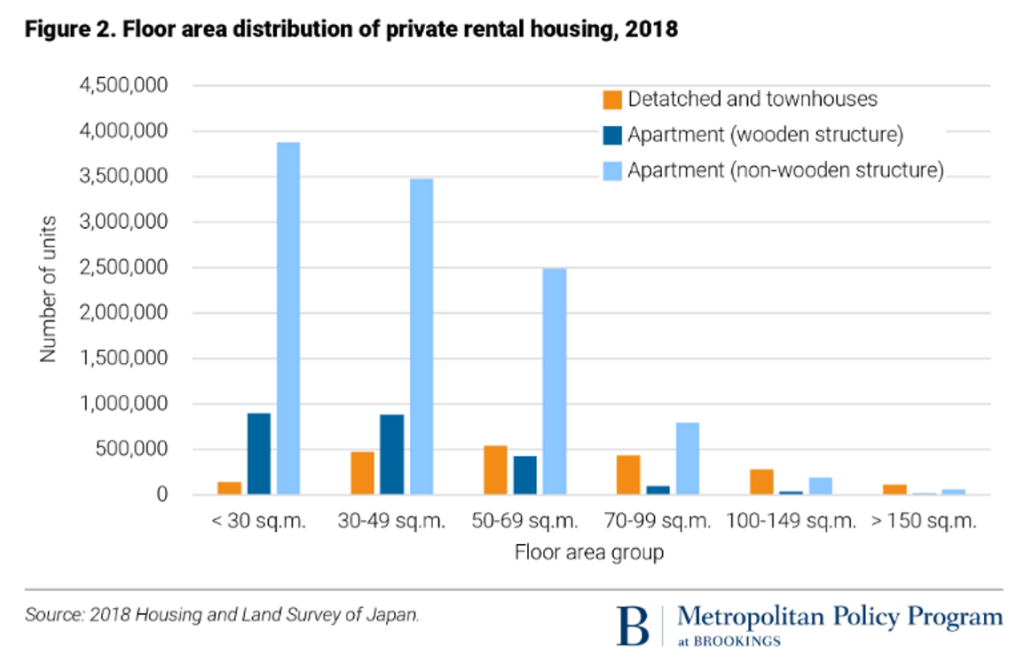

The net effect of this much housing construction appears to be lower housing expenditures. According to the Brookings article: “The average ratio is about 16% for homeowners, 13% for renters, 10% for public housing renters, and 4% for subsidized corporate housing renters.” However it’s important to note that unit sizes tend to be fairly small as shown below. Although in CAD, the rents in Tokyo Metro range from approximately average $2.0 PSF per month for wood frame and $2.6 PSF per month for non-woodframe, still significantly lower than Canadian major metropolitan rents. It’s important to note that while the Japanese population is in decline, the core Tokyo area continues to see population increase.

Final Remarks and comparison with BC:

The Japanese tenancy system differs significantly from that in BC. There is little regulatory emphasis on rent control, and rent-setting largely follows market trends. At the same time, tenant protection comes through procedural rights — especially regarding lease renewals — rather than through pricing regulation. The requirement for court action to deny renewal or to evict creates an incentive for landlords to use fixed-term contracts or seek tenants unlikely to remain long-term. This somewhat skews the type of housing supply that is available on the rental market – more smaller units suitable for single people rather than family sized units.

What stands out most is the extensive list of fees and deposits paid by tenants at lease commencement — key money, agent commissions, renewal fees — which are not typically rolled into rent. Despite their complexity, these payments remain broadly accepted in Japanese leasing. Furthermore, as like in Germany, certain operating costs for residential tenancies can be negotiated and shared between owner and tenant.

We find the Japanese regulatory system around tenancies to be less straight forward and more complex than the German system. However, the biggest difference that seems to impact rental housing outcomes appears to be the speed and volume of housing supply provision in Japan.

Sources used in no particular order, where otherwise not cited:

1. FT article on Japan housing supply: https://www.ft.com/content/023562e2-54a6-11e6-befd-2fc0c26b3c60

2. Sorensen, A. (2003). Building world city Tokyo Globalization and conflict over urban space. The Annals of Regional Science, 37(3), 519–531. doi10.1007s00168-003-0168-3.pdf

3. Tenlaw Japan: https://arquivo.pt/wayback/20160421110935/http:/www.tenlaw.uni-bremen.de/brochures.html

4. Guide to Renting in Japan: https://www.sasn.jp/pdf/hi_english.pdf

5. Zoning in Japan: https://urbankchoze.blogspot.com/2014/04/japanese-zoning.html

6. Greater London Authority – https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/london_shma_2017.pdf

7. Sightline – https://www.sightline.org/2021/03/25/yes-other-countries-do-housing-better-case-1-japan/

8. Brookings – https://www.brookings.edu/articles/Japan-rental-housing-markets/

Disclosure/Disclaimer:

This blog is published by Habit8 Property Management, licensed property managers in British Columbia. The information provided is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, financial, tax, or other professional advice. While we strive to ensure accuracy, the content reflects our understanding as of the date of publication and may not account for future changes in laws, regulations, or market conditions. You should consult appropriate professionals before making any decisions based on this content.

Get in touch

Was this interesting?

Let us know!