NewsWhat are the impact of tenant protection policies on rents?

Do Tenant Protections Raise Rents? Evidence from U.S. State Laws

Tenancy regulations have changed in North America in response to rising rents and displacement concerns. But how do policies that attempt to protect tenants affect broader housing market outcomes like rent levels, housing supply, and eviction rates?

A 2020 study by Coulson, Le, and Shen uses a mix of theoretical modeling and empirical analysis to evaluate the trade-offs. The findings are interesting: stronger tenant protections reduce evictions, but also correlate with higher rents, lower vacancy, reduced rental supply, and higher homelessness.

Overview of the Approach

The authors develop a model of the rental market, where landlords can evict “bad tenants” but face legal and financial costs. These costs are tied to statutory tenant protections. The model predicts that higher eviction costs (i.e. stronger tenant laws) will reduce eviction rates but also lead landlords to raise rents and exit the rental market.

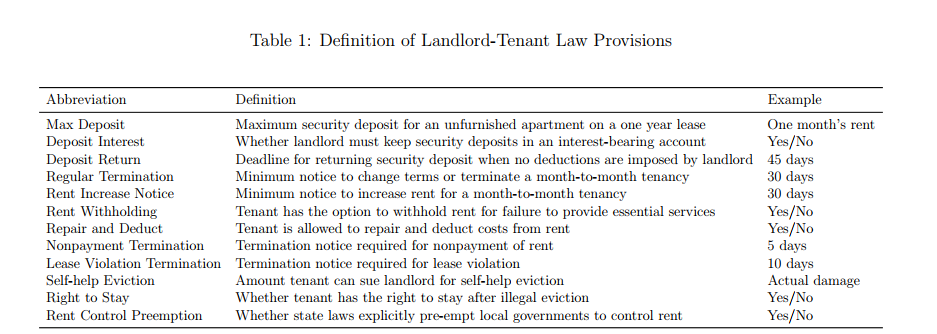

To test this, the authors construct a Tenant Rights Index (TRI) across U.S. states from 2005–2016 based on twelve aspects of landlord-tenant law. These are the following:

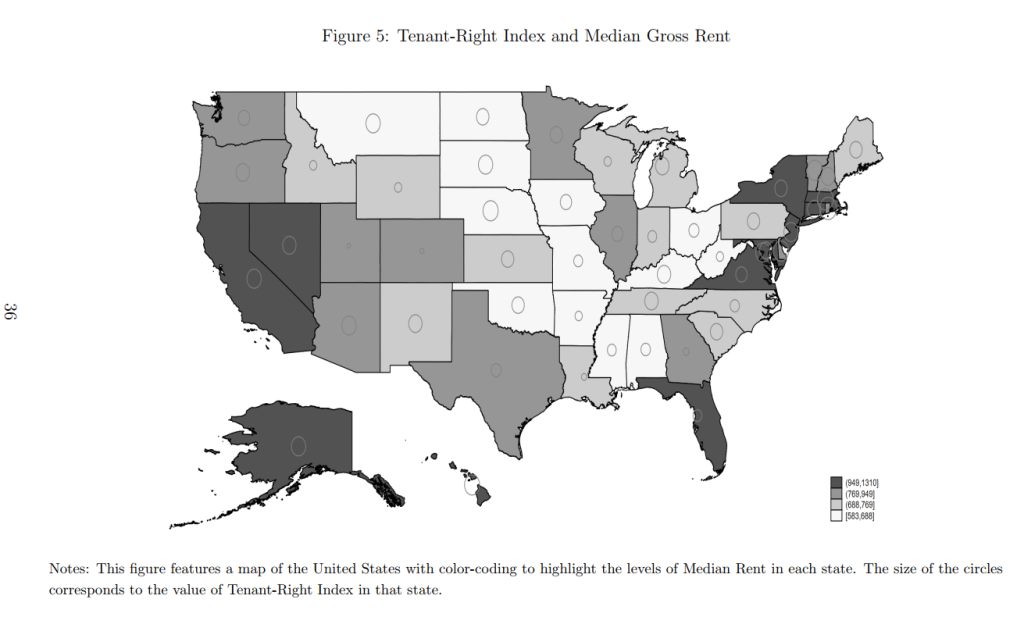

States score 1 point for each tenant-favorable provision (e.g. >30-day notice required for regular termination), for a total possible score of 12. Scores above 6 are classified as “tenant-friendly” — 22 states meet this threshold.

The authors then test this TRI against data from 2005-2016. Rent data comes from census surveys of gross rent at the city level which is contract rent plus estimated utilities as well as data from Zillow. Vacancy rates are from the US census and are at city level. Eviction rates are from a large dataset from Princeton University Eviction Lab. Homelessness rates are from the Annual Homeless Assessment Report from the US HUD at the state level. And rental housing supply is from the census at the city level.

To address endogeneity, the paper uses Democratic vote share in presidential elections as an proxy for tenant friendliness and found that this also correlated with the findings of the Tenants Rights Index. This is based on the assumption that Democratic-leaning states are more likely to pass tenant protection laws. However, this raises questions: Democratic-voting areas tend to include larger urban centers with higher zoning barriers and housing demand, which may themselves drive rent increases. Traditional demographic strongholds such as New York and California are also just bad at providing housing supply compared to more right leaning states like Texas and Florida. Note that however the study authors did try to control for local demographics: population, population growth, population density, median household income, HH income growth, home ownership rate, and property characteristics at city level: median number of rooms, median property age, median property tax paid. Furthermore, the analysis is done at the state level, which may balance out urban and non-urban effects

Main Results

- Rents: A weak but positive relationship exists between stronger tenant protections and higher median gross rent (rent + utilities). A 1-point increase in the TRI corresponds to roughly a 6% increase in rent in the IV model.

- Rental supply: A 1-point increase in TRI is associated with a 1.4% reduction in rental supply, measured as the number of rental units per 100 residents. This aligns with prior findings that stricter regulations lead landlords to exit the market—by converting units to owner-occupied, not building new rental, or selling to end users.

- Evictions: Eviction data from Princeton’s Eviction Lab shows a negative relationship between TRI and eviction rate. A 1-point increase in TRI corresponds to an 8.9% drop in eviction judgments. The effect is stronger in places where tenant protections are already robust.

- Vacancy rates and homelessness: Stronger tenant laws are associated with lower rental vacancy rates and higher homelessness—likely a result of constrained supply rather than direct policy effects.

Policy Takeaways

The authors do not argue against tenant protections but the data highlight a trade-off: while tenant protections may reduce formal evictions, they may also raise rents, reduce housing supply, and as a byproduct of less housing, actually increase homelessness.

This mirrors what has been found in studies of rent control: they benefit incumbent tenants at the cost of worse affordability and access for new entrants. U.S. rent control laws typically exempt new construction to avoid some of these supply impacts—something worth considering in broader tenant protection reforms.

When cities or regions are faced with increased demand for housing and there’s upwards pressure on rents, it can be politically advantageous to address the symptoms of the issue: rents going up -> disallow or cap rent increases, evictions increasing to turn over tenancies -> disallow or penalize different forms of evictions. What this paper seems to show is that there are costs to these policies and those costs incentivize people to reduce rental housing supply, whereby increasing market rents.

Furthermore in our experience, limited deposits, lengthy eviction processes, and limited recourse against bad tenants typically cause rental housing providers to increase the rigour of their screening which benefits well qualified tenants with steady incomes, good credit and backgrounds at the expense of new comers and those with lower incomes. For example, a tenant without much credit history may wish to offer a larger deposit or to prepay some amount of rent upfront, but this is not allowed under BC’s RTA.

Comparison: How Would BC Score on the Tenant Rights Index?

To contextualize the U.S. findings, it’s worth comparing British Columbia’s tenancy laws to the 12-point framework used in the TRI.

| Policy Element | BC Status | TRI Score Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Max Deposit | ½ month’s rent | 1 |

| Deposit Interest | Yes | 1 |

| Deposit Return Deadline | 15 days after move-out | 1 |

| Regular Termination | 2-4 month notice for owner move-in or renovation | 1 |

| Rent Increase Notice | 3 months | 1 |

| Rent Withholding | Not allowed without RTB judgement | 0 |

| Repair and Deduct | Not allowed without RTB judgement | 0 |

| Nonpayment Termination | 10-day notice for nonpayment | 1 |

| Lease Violation Termination | Usually 1-month notice (for cause) | 1 |

| Self-Help Eviction Penalty | Penalty of up to $5000 plus damages | 1 |

| Right to Stay after Illegal Eviction | Yes | 1 |

| Rent Control Preemption | N/A the province sets rent control | 1 |

Estimated BC TRI Score: 10 out of 12

This would place BC as number 2 – tied with Massachusetts (10), and only below Rhode Island (11). Although my critique of the Tenants Rights Index is giving equal weigthing of all 12 factors when something like whether interest is owed on deposits is far less impactful than Rent Control. I wonder how the results may change with some adjustments to the TRI.

Source:

N. Edward Coulson, Thao Le, Victor Ortego-Marti, Lily Shen,

Tenant rights, eviction, and rent affordability,

Journal of Urban Economics,

Volume 147,

2025,

103762,

ISSN 0094-1190,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2025.103762.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094119025000270)

Disclosure/Disclaimer:

This blog is published by Habit8 Property Management, licensed property managers in British Columbia. The information provided is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, financial, tax, or other professional advice. While we strive to ensure accuracy, the content reflects our understanding as of the date of publication and may not account for future changes in laws, regulations, or market conditions. You should consult appropriate professionals before making any decisions based on this content.

Get in touch

What this interesting?

Let us know!