NewsComments on a recent paper on “financialization” in rental housing

Financialization Paper:

This recent research paper out of the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo got picked up by the media (here, and here) and got our attention. We think that the entire discourse around ‘financialization’ as a problem when it comes to housing supply is misguided and counterproductive. It misdiagnosis the issue around housing and prescribes solutions which will likely harm the provision of housing supply. Nevertheless we’re always interested in what’s shaping public opinion around rental housing and open to new information and ideas.

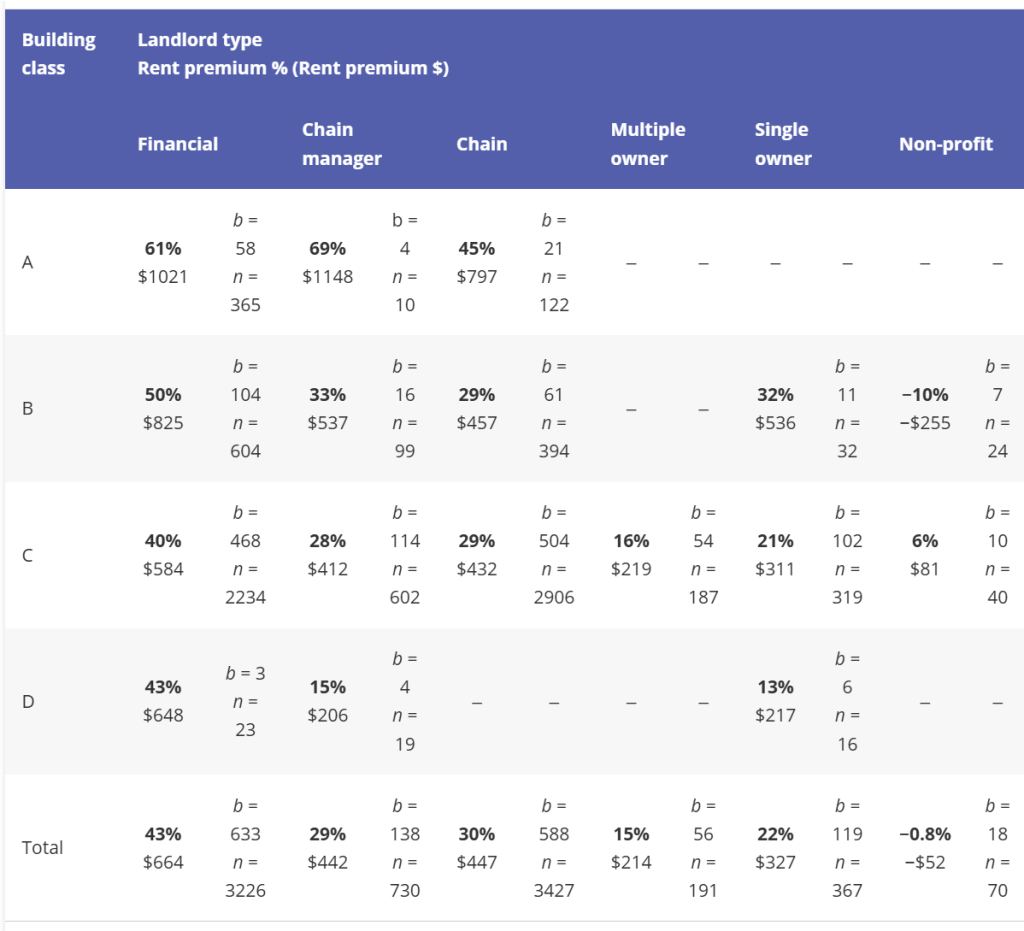

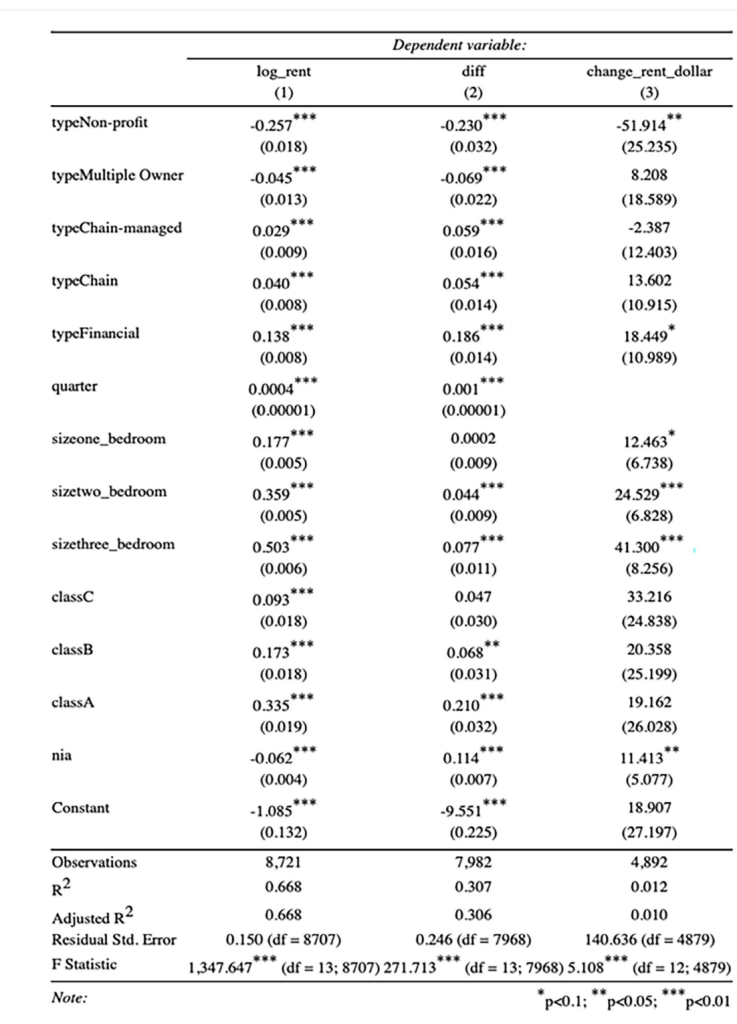

The study claims, by examining Toronto rental data, that they find larger ‘financialized’ owners of rental buildings tend to charge higher rents, by 10-20% or so, than other types of owners, and while tries to claim they control for building class, doesn’t go deeply into building quality variations. In fact their regression only includes the following variables: type of owner, class of building, size of unit, time, and whether the building was in a Neighbourhood Improvement Area (NIA). They didn’t even include the age of the building. It’s often seen that larger institutional owners invest in newer highrise concrete, more premium buildings with more amenities compared to the market as a whole which can include many older wood frame rentals. Nor do they look at the location of buildings as they relate to ownership. It is plausible that in the areas with highest rents in Toronto, the only buildings that are possible to build are large high density projects which require large investments typically only large ‘financialized’ firms can undertake.

They define the owner categories as follows which essentially makes any large investor a ‘financial’ firm because they pool capital.

Non-profit: Social or not-for-profit owner;

Single Owner: People or corporate entities that owned one property;

Multiple Owner: People or corporate entities that owned more than one property;

Chain Managed: Single or Multiple Owners that used a third-party property manager (e.g. Briarlane, Berkley, Greenwin, MetCap, Sterling Karamar), providing sophistication and scale of operations not normally accessible to smaller scale owners;

Chain: Corporations that own multiple residential buildings under a visible brand name, that typically have a website (e.g. Medallion, Park Property Management). This includes family-run or private companies not accessible to outside investors.

Financial: Any firm that makes property available to third-party investors, including REITs, publicly-listed companies, private equity, asset managers, institutions (pension funds, and insurance companies) (e.g. Starlight Investments, CAPREIT).11

From <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0308518X251328129>

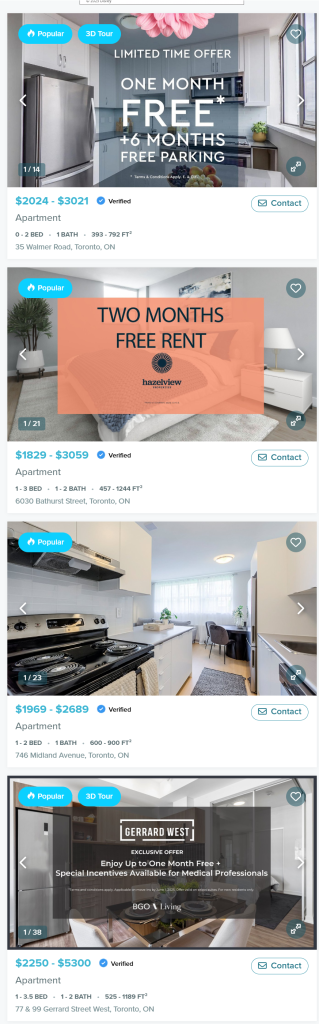

Furthermore, the study’s authors only rely on asking rent data from 2022-24 with no mention of any adjustments for move-in incentives like 1 or 2 months free rent which are far more often offered by institutional landlords rather than smaller players because of their reporting requirements. Anyone taking a look at rental listings in Toronto will see these ‘incentives’ are everywhere especially as the market softened in ’24. Some examples of rental listings in toronto from rentals.ca below:

Regardless of potential data shortcomings, here’s what they found. Some of the biggest problems with this data remains that they don’t control well for quality of building differences, location of buildings, and effective vs asking rent.

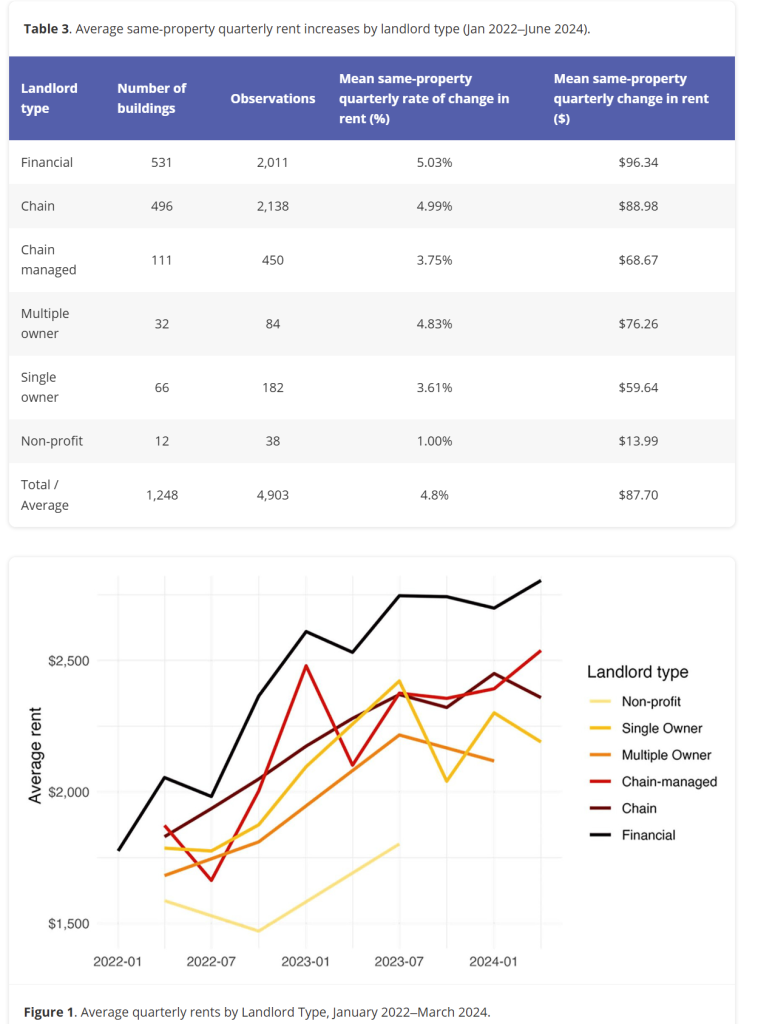

The study also looked at same building rent increases over time, here there was far less of a difference, or essentially none at all between ‘financial’, ‘chain’, and ‘multiple owner’ as it better controls for building to building or portfolio variations. But the data still suffers from differentiated growth rates based on the type of product and where larger ‘financial’ owners may invest and the difference between asking and effective rents net of incentives. It’s shown on the charter that in early 2024 – both multi and single owner rents dropped whereas chain & financial continued to increase – this can very much be due to the study’s authors not accounting for incentives as the market started to weaken.

Furthermore, there is the matter of investment strategy. The authors write:

We associate high same-property rent increases with a strategy of value-add repositioning, often targeting lower-cost (Class C) properties where firms see the most runway (to use an industry term) to raise rents. These are areas where landlords capitalize on the rent gap (to use an academic term) between low existing and high potential rents (Smith, 1987). Financial firms may create conditions for pushing ‘potential’ rents even higher, drawing on supply constraints, superior market intelligence, technology, and capital to create (and close) a bigger rent gap.

And later on:

In other words, the firm targets low-cost rentals as ‘dislocations’ and drives value for shareholders by systematically closing the gap between existing and potential rents in the gentrifying community.

From <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0308518X251328129>

Private equity owners probably tend to employ value-add strategies more often than smaller property owners, and they typically go into a project with an investment strategy that involves renovating and repositioning properties which are perceived to be undervalued and mismanaged. Furthermore, some value add strategies may simply involve buying out rent-controlled tenants – the cost of which the study’s authors have not included in their analysis.

In their regression results, their least problematic calculation of the change in same building rents does not seem to show strong statistical evidence to back the authors claims.

Later in the paper, the authors then tied the issue to social justice by writing:

These maps suggest that in low-income and racialized communities, landlords seek bigger revenue gains from devalued rental properties, using repositioning and ‘value add’ strategies to extract higher rents and fees from lower-income renters (August and Walks, 2018).

From <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0308518X251328129>

The city of Toronto named these NIAs – Neighbourhood improvement areas – because they wanted to target them for increased investment in services and infrastructure, both public and private. If private sector investors are participating in these areas and improving the supply of housing – it’s a natural consequence that market rents may be higher after the investment in improvement in services and housing. However, it appears that the authors of the study seem to think that improvements in living conditions that result in higher willingness to pay from renters is a bad outcome and one to be avoided.

In Conclusion

The conclusion of the paper reads:

Financial firms are leading the industry in raising rents and worsening housing affordability. This matters because they continue to dominate in apartment ownership, acquiring almost all suites sold in Toronto in recent years. Our findings suggest that the more they own, the worse affordability will get. We echo policy recommendations to rein in financial firms in the interests of promoting affordability (Farha et al., 2022; August, 2022). Notably, our findings should not be taken as an endorsement of non-financial landlords (Bano, 2024), who similarly (although not to the same degree) engage in rent-raising behaviours. As financial firms set the standard in the industry, other firms will increasingly follow their lead—adopting the strategies and technology associated with high rent increases. Ultimately, the social relation between tenants and landlords ensures exploitation and the solution involves regulating rental housing, expanding tenant protections, and replacing for-profit ownership with social housing—efforts that will support tenants and housing equality regardless of landlord type.

From <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0308518X251328129>

When we break this down:

“Financial firms are leading the industry in raising rents and worsening housing affordability. This matters because they continue to dominate in apartment ownership, acquiring almost all suites sold in Toronto in recent years.”

- They may have shown that large firms tend to own higher priced rentals, which can be due to location, building amenities, building age & quality that the authors don’t control for, but that does not mean that it worsens housing affordability. Because buildings do not get built without investment, and to the extent that these companies financed the construction of new rental supply, their impact is probably in lowering the market rent across the board

- And regarding ‘financial firms’ owning a majority of new large rental buildings – this is likely because in Toronto where most new construction is fairly high density large projects of over $100m and require large investors or pooled capital

“Our findings suggest that the more they own, the worse affordability will get.”

- This is an unfounded conclusion and defies logic. Do they mean to say that the more rental apartment investment, development and construction happens, the worse affordability will get simply because ‘financial firms’ own them?

- That if ownership of the properties were transferred to some government entity – affordability would be magically restored? Rather than simply trading market pricing and free-exchange for waitlists and less efficient government allocation of resources.

- And let’s say we prevented the companies from deploying a value-add strategy whereby renovating older units to supply higher quality housing, all that ensures is that we get slightly lower rents because the quality of housing is worse. It’s like shunning new cars because they cost more than old cars, which when it essentially happened during covid’s supply chain chaos – used cars exploded in value because of the shortage of new cars

“We echo policy recommendations to rein in financial firms in the interests of promoting affordability (Farha et al., 2022; August, 2022). Notably, our findings should not be taken as an endorsement of non-financial landlords (Bano, 2024), who similarly (although not to the same degree) engage in rent-raising behaviours. As financial firms set the standard in the industry, other firms will increasingly follow their lead—adopting the strategies and technology associated with high rent increases.”

- Here the authors also do not forget to criticize the other housing providers as well, who participate in a market based housing wherein changes in supply and demand dictate the rent

“Ultimately, the social relation between tenants and landlords ensures exploitation and the solution involves regulating rental housing, expanding tenant protections, and replacing for-profit ownership with social housing—efforts that will support tenants and housing equality regardless of landlord type.”

- Ultimately, the authors appear to have the view that market based economies, and the free exchange of the use of housing for money, “ensures exploitation”

- The solution to this in the authors view is to replace free market housing with social housing, owned and allocated by some government entity

- Nowhere in the entire paper is there mention of increasing the supply of housing

My general take is that the researchers could benefit from actually engaging with housing providers, developers, and investors – both in the for-profit and non-profit side – if they really wanted to try and solve problems and produce useful research. Planning departments and cities around the country seem to be struggling with increased costs of services, challenges planning for infrastructure, and slow and bureaucratic approval processes. These are the concrete problems which need to be worked on to ultimately greater benefit our society and university planning departments which train future generations of public sector leaders can play a more helpful role in this regard.

Disclosure/Disclaimer:

This blog is published by Habit8 Property Management, licensed property managers in British Columbia. The information provided is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, financial, tax, or other professional advice. While we strive to ensure accuracy, the content reflects our understanding as of the date of publication and may not account for future changes in laws, regulations, or market conditions. You should consult appropriate professionals before making any decisions based on this content.

Get in touch

We believe in free markets and the role of the private sector in housing

Let us know if you agree